India is turning from man to machines to improve the quality and speed of its economic data, which has been criticized as inadequate, delayed or even confusing due to sharp and unexpected revisions.

The Ministry of Statistics is ramping up use of artificial intelligence for collecting, analyzing and reporting data to better monitor the economy. The measures include a $60 million program with World Bank help using an information portal that collates real-time data.

“Because of the changing landscape, there’s a growing need for more and more data, faster data and also more refined data products,” Statistics Secretary Kshatrapati Shivaji said in an interview. With end-to-end computerization, “this type of automation will enhance the quality, credibility and timeliness of data.”

The quality of its economic numbers is a pressing issue for India following numerous controversies over its data. While the pandemic has exposed the constraints of conventional economic data the world over, the problem is particularly acute in India, where a dependence on manual processing has sometimes led to a data vacuum.

The country of 1.3 billion people, only 20% of whom know how to use the internet, had to suspend field surveys during the lockdown, which led to gaps in reporting monthly retail inflation numbers. The missing information eventually was filled in with phone surveys, but the ministry is also establishing a system to do surveys electronically, and will use digital databases where possible.

“Apart from using such data from a policy perspective, having access to updated data can be used to suggest leads for sector-specific interventions, immediately, as and when required,” said GV Anand Bhushan, Chennai-based partner at the Shardul Amarchand Mangaldas & Co. law firm, which is advising some technology companies working with the government.

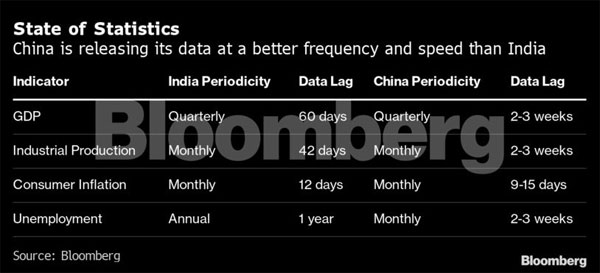

India is seeking to build its manufacturing sector by wooing companies away from China, but it can’t compare to Asia’s biggest economy in timely reporting of statistics. India’s quarterly GDP data are reported with a lag of two months, compared to less than three weeks in China.

The situation is worse for India’s jobs statistics, a burning issue in a country where about 1 million people enter the job market every month. While the U.S. and China, which has been accused of massaging its economic data to meet political goals, release monthly jobs numbers, Indian employment statistics are already a year out of date by the time they’re reported.

“This is an ongoing challenge for investors in India,” said Joevin Teo, head of Asia fixed-income at Amundi Singapore Ltd. Having higher-frequency data such as employment and retail sales, as well as third-party data that could be checked against official statistics, would “help fund managers avoid a scenario where economic data and on-the-ground reality are inconsistent.”

It doesn’t seem to be deterring international investors, however: They’ve poured about $24 billion into Indian stocks over the past 12 months, while pulling money out of other Asian economies except China’s, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

Given concerns about the official data, economists who study India are seeking alternatives. Monthly numbers released by Mumbai-based private research firm Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy, which does its own surveys, have become the de-facto unemployment data. Many analysts, including Bloomberg Economist Abhishek Gupta, use their own tools to take the economy’s pulse.

“Advancements in information and communication technology and the rapid digitalization of society have created new opportunities for India to improve its national statistical system,” a spokesman for the World Bank said. “COVID-19 has further underscored the need for modernization as the pandemic and associated lockdowns upended traditional methods of data collection.”

India’s GDP data has been at the center of debate since 2015, when the government revised the base year to reflect changes in the economy. The intention was to capture the latest developments — including the replacement of obsolete items such as typewriters that have made way for smart devices — but the suddenly higher growth rate puzzled economists.

On top of other issues, India’s statistics departments face a manpower shortage: Looking at statistical officers posts in different ministries and states, 2,013 of 7,363 positions are vacant.

The Statistics Ministry’s Shivaji said artificial intelligence will be used “extensively” and can help overcome personnel constraints.

“Because of automation and technology-intensive applications, the capability and productivity of staff is getting enhanced substantially,” he said. “Wherever there is a component where we’re able to squeeze the time with the help of technology, we’re trying to do that.”

Source : PTI